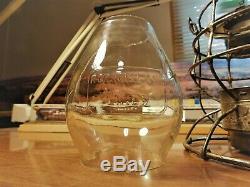

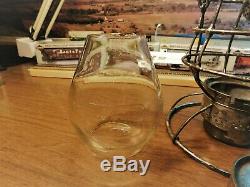

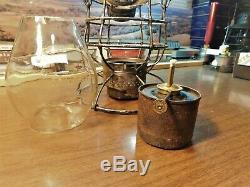

Rock Island Railroad Lantern Adams & Westlake Company Rock Island Line 1895

CHICAGO ROCK ISLAND & PACIFIC RAILROAD. This is a Vintage piece of Railroad History made by THE ADAMS & WESTLAKE COMPANY for the CHICAGO ROCK ISLAND & PACIFIC RAILROAD.

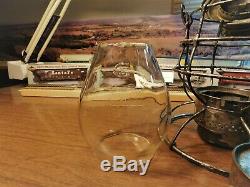

This lantern is marked THE ADAMS AND WESTLAKE COMPANY CHICAGO NEW YORK ROCK ISLAND LINES. The lantern is numbered 15770.The brass burner is marked E. And is in good working condition. The Corning clear glass globe is embossed ROCK ISLAND LINES Cnx 2, No cracks some chips around the rims. Fuel font has some repair work on the bottom.

Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The Rock Island System in 1965.

October 10, 1852March 31, 1980. Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway. It was also known as the. Rock Island Line , or, in its final years. Those totals may or may not include the former. The song Rock Island Line. , a spiritual from the late 1920s first recorded in 1934, was inspired by the railway. Rock Island's survival challenge. The Rock Island's last attempt to survive. Rock Island locomotive #627, circa 1880. Rock Island and La Salle Railroad Company , was incorporated in Illinois on February 27, 1847, and an amended charter was approved on February 7, 1851, as the. Chicago and Rock Island Railroad. Construction began October 1, 1851, in Chicago, and the first train was operated on October 10, 1852, between Chicago and. Was reached on February 22, 1854, becoming the first railroad to connect Chicago with the Mississippi River. In Iowa, the C&RI's incorporators created (on February 5, 1853) the. Company (M&M), to run from.And on November 20, 1855, the first train to operate in Iowa steamed from Davenport to. The Mississippi river bridge between Rock Island and Davenport was completed on April 22, 1856. The former Rock Island Depot at. Represented the Rock Island in an important lawsuit regarding bridges over navigable rivers. The suit had been brought by the owner of a steamboat which was destroyed by fire after running into the Mississippi river bridge.

Lincoln argued that not only was the steamboat at fault in striking the bridge but that bridges across navigable rivers were to the advantage of the country. The M&M was acquired by the C&RI on July 9, 1866, to form the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad Company. The railroad expanded through construction and acquisitions in the following decades. The Rock Island stretched across.

The easternmost reach of the system was. And the system also reached. While in a northerly direction the Rock Island got as far as. Major lines included Minneapolis to.To Santa Rosa via Kansas City. And Santa Rosa to Memphis. The heaviest traffic was on the Chicago-to-Rock Island and Rock Island-to-Muscatine lines.

Rock Island E-8 #652 with E-6 #630 at Midland Railway, Baldwin City, KS. In common with most American railroad companies, the Rock Island once operated an extensive passenger service. The primary routes served were: Chicago-Los Angeles, Chicago-Denver, Memphis-Little Rock-Oklahoma City- Tucumcari. The Rock Island ran both limited and local service on those routes as well as locals on many other lines on its system.

At 99th Street in Washington Heights on the Rock Island mainline in April 1965. The Rock Island jointly operated the. (ChicagoKansas CityTucumcariEl PasoLos Angeles) with the.

On this route, the Rock Island's train was marketed as a "low altitude" crossing of the. The Rock Island did not concede to the. Travel market and re-equipped the train with new streamlined equipment in 1948. At the same time, the "Limited" was dropped from the train's name and the train was thereafter known as the. The local run on this line was known as the. Once part of the Rock Island system. The 1948 modernization of the.In 1947, both the Rock Island and Southern Pacific jointly advertised the coming of a new entry in the Chicago-Los Angeles travel market. The Rock Island's cars were delivered and would find their way into the. Was the last first-class train on the Rock Island, retaining its.

Until its last run on February 21, 1968. The Rock Island also competed with the. Railroad in the Chicago to Denver market. While the Q fielded its Zephyrs on the route, the Rock Island ran the. With half the train diverting to.An operation known as "The Limon Shuffle". The Rock Island conceded nothing to its rival, even installing ABS signaling on the route west of Lincoln in an effort to maintain transit speed. The train was also re-equipped with streamlined equipment in 1948.

Was downgraded due to non-rail competition, the route traveled by the train was shortened from the western terminal at Denver, first to Omaha, then to Council Bluffs and the train was renamed. In 1970, the train was cut to a Chicago to Rock Island run, a run entirely within the confines of the state of Illinois and finally renamed the. Other trains operated by the Rock Island as part of its Rocket fleet included the. PaulDes MoinesKansas CityOklahoma CityFort WorthDallasHouston, the.

(MemphisLittle RockOklahoma CityAmarillo) and the. (a local counterpart to the Choctaw Rocket, Memphis-Little Rock-Oklahoma City-Amarillo-Tucumcari-Los Angeles). One of the last passenger timetables issued by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. The Rock Island did not join Amtrak on May 1, 1971, and continued to operate its own passenger service until 1978.

The Rock Island did not join. On its formation in 1971, and continued to operate its own passenger trains. After concluding that the cost of joining would be greater than operating the two remaining intercity (and now intrastate) roundtrips the Chicago-Peoria. Quad Cities Rocket , the railroad decided to "perform a public service for the state of Illinois" and continue intercity passenger operations. To help manage the service, the Rock Island hired.National Association of Railroad Passengers. As Managing Director of Passenger Services. The last two trains plied the Rock Island's Illinois Division as the track quality declined from 1971 through 1977. The transit times, once a speedy 2½ hours in the 1950s, had lengthened to a 4½ hour run by 1975.

The State of Illinois continued to subsidize the service to keep it running. The track program of 1978 helped with main line timekeeping, although the Rock Island's management decreed that the two trains down to two coaches and an aged. With the trains frequently running with as many paying passengers as coaches in the train, the state withdrew the subsidy and the two trains made their final runs on December 31, 1978. The Rock Island also operated. Service in the Chicago area. The primary route ran from. To Joliet along the main line, and a spur line, known as the "Suburban Line" to Blue Island. The main line trains supplanted the long-distance services that did not stop at the numerous stations on that route. The Suburban Line served the Beverly Hills area of Chicago as a branch leaving the main line at Gresham and heading due west, paralleling the.Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad. Passenger line before turning south. The Suburban Line made stops every four blocks along the way before rejoining the Main Line at Western Avenue Junction in Blue Island.

From the 1920s on, the suburban services were operated using Pacific-type. Locomotives and specially designed light-heavyweight coaches that, with their late 1920s build dates, became known as the Capone. The suburban service became well known in the diesel era, as the steam power was replaced, first with new. Built 2700-series cars arrived as the first air conditioned commuter cars on the line.In the 1960s, the Rock Island tried to upgrade the suburban service with newer equipment at lower cost. Power for these new cars was provided by orphaned passenger units: three. The power was rebuilt with.

To provide heat, air conditioning, and lighting for the new cars. In 1970, another order, this time for Pullman-built bilevel cars arrived to further supplement the fleet. To provide the power for these cars, several former. Diesels were rebuilt with head end power and added to the commuter pool. The outdoor passenger concourse and platforms of LaSalle Street Station as built and operated by. The trains shown are commuter runs to. The commuter service was not exempt from the general decline of the Rock Island through the 1970s. Over time, deferred maintenance took its toll on both track and rolling stock.On the Rock Island, the Capone cars were entering their sixth decade of service and the nearly 30-year-old 2700s suffered from severe corrosion due to the steel used in their construction. The service's downtown terminal, suffered from neglect and urban decay with the slab roof of the train shed literally falling apart, requiring its removal. By this time, the Rock Island could not afford to replace the clearly worn-out equipment. In 1976, the entire Chicago commuter rail system began to receive financial support from the State of Illinois through the. Operating funds were disbursed to all commuter operators and the Rock Island was to be provided with new equipment to replace the tired 2700 series and Capone cars.

New Budd bilevels that were near copies of the 1961 Milwaukee Road cars arrived in 1978. Units arrived in late 1977 and, in summer, 1978, briefly could be seen hauling Capone cars.

With the 1980 end of the Rock Island, the. Was torn down and replaced with the. Building with a small station for commuters retained one block south of the old station. The RTA gradually rebuilt the track and added more new equipment to the service, leaving the property in better shape than it was in the Rock Island's heyday, albeit with less track.

As the Rock Island's suburban service is now known, now operates as part of. The Chicago Commuter Rail agency. As the glory years of the Farrington era waned in the late 1950s, the Rock Island found itself once again faced with flat traffic, flat revenues and increasing costs.

The property was still in decent shape and the Rock Island made an attractive bride for a rail suitor looking to expand the reach of their current system. The Rock Island was known as "one railroad too many" in the plains states, basically serving the same territory as the.

Only over a longer route. The midwest rail network had been built in the late 19th century to serve that era's traffic. The mechanization of grain hauling gave larger reach to large. Reducing the need for the tight web of track that crisscrossed the plains states such as.

As for available overhead traffic, in 1958 there were no less than six Class I carriers serving as eastern connections for the. All seeking a slice of the flood of western traffic that UP interchanged there. Under the ICC revenue rules in place at the time, the Rock Island sought traffic from Omaha, yet preferred to keep the long haul to. Where interchange could be made with the.Denver and Rio Grande Western. For haulage to the west coast.

The only option for the Rock Island to grow revenues and absorb costs was to merge with another, perhaps more prosperous railroad. Overtures were made from fellow midwest. Both of these never advanced much beyond the data gathering and initial study phases. In 1964 - its last profitable year. To pursue a merger plan to form one large "super" railroad stretching from Chicago to the West Coast.

With these filings began the longest and most complicated merger case in. Faced with failing granger railroads and large Class I railroads seeking to expand, ICC Hearing Examiner Nathan Klitenic, presiding over the case, sought to balance the opposing forces and completely restructure the railroads of the United States west of the. After ten years of hearings and tens of thousands of pages of testimony and exhibits produced, now-Administrative Law Judge Nathan Klitenic approved a plan for rail service throughout the west to be covered by four mega-systems: The Chicago-Omaha main would go to the Union Pacific. The visionary plan would not be realized until the mega-mergers of the 1990s with the.

Remaining as the two surviving major rail carriers west of the. During most of the ensuing merger process, Rock Island operated at a financial loss. In 1965, Rock Island would earn its last profit. With the merger with Union Pacific seemingly so close, the Rock Island cut expenses to conserve cash. Expenditures on track maintenance were cut, passenger service was reduced as fast as the ICC would allow, and locomotives received only basic maintenance to keep them running.Rock Island began to take on a ramshackle appearance and derailments occurred with increasing frequency. In an effort to prop up its future merger mate, UP asked the Rock Island to forsake the Denver gateway in favor of increased interchange at Omaha. Incredibly, the Rock Island refused this and the UP routed more Omaha traffic over the.

By the time of the 1974 approval of the merger, Rock Island was no longer the attractive bride it had once been in the 1950s. The Union Pacific viewed the cost to bring the property back to viable operating condition to be prohibitive. The conditions attached to the agreement for both labor and operating concessions were also viewed as excessive. Union Pacific simply walked away from the process, ending the merger case.In 1974, the road adopted a new color scheme proclaiming The Rock. When the Rock Island shut down in 1980, and became MoPac #2278. Now set free and adrift, both operationally and financially, the Rock Island assessed their options. Rock Island hired a new president and CEO.

Ingram quickly sought to improve efficiency and sought FRA loans for the rebuild of the line, but finances caught up with the Rock Island all too quickly. Was selected as receiver and trustee by Judge Frank J. McGarr, with whom Gibbons practiced law in the early 1960s. With its debts on hold, Rock Island charted a new course as a grain funnel from the mid-West to the port of. Cabooseless grain shuttles were one cost effective way to gain market share and help finance the plan internally.

Nevertheless, new and rebuilt locomotives arrived on the property in gleaming blue and white to replace some of the tired, filthy power. Track rebuild projects covered the system. Main lines that had seen little or no maintenance in years were pulled from the mud. Rail and tie replacement programs attacked the maintenance backlog.

However, the FRA-backed loans that Ingram sought were thwarted by the lobbying efforts of competing railroads, who considered a healthy Rock Island as a threat. By 1978, main line track improved in quality. The sale of the Golden State Route to the Southern Pacific had been agreed to. The Rock Island slowly inched towards a financial break-even point, despite the financial malaise that plagued the late 1970s. Advocated for the shutdown and liquidation of the property.Crown declared that the Rock Island was not capable of operating profitably, much less paying its outstanding debts. At the same time, Crown invested as much as he could in Rock Island bonds and other debt at bankruptcy-induced junk status prices.

For the previous two years, while the Rock Island invested heavily into its physical plant, the Rock Island brotherhoods had been working under expired labor agreements. The front line operating employees had not had an increase in pay since the existing contracts expired yet remained on the job during extensive contract negotiations. By the summer of 1979, the. Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks. (BRAC) held firm to their demand that pay increases be back dated to the expiration date of the previous agreement.

The Rock Island offered to open the books to show the precarious financial condition of the road in an effort to get the BRAC in line with the other unions that had already signed agreements. Kroll, president of the BRAC, declined the offer to audit the books of the Rock Island. Kroll pulled his BRAC clerks off the job in August, 1979.

Picket lines went up at every terminal on the Rock Island's system and the operating brotherhoods honored the picket lines. The Rock Island ground to a halt. The Ingram management team operated as much of the Rock Island as they could. Trains slowly began to move, with more traffic being hauled every week of the strike.Issued a back-to-work order that BRAC dismissed. Still more traffic flowed on the strikebound Rock Island. In other words, the company was winning the strike.

Seeing the trains rolling despite the strike and fearing a. Strikebreaking situation, the unions appealed to the FRA and ICC for relief. Despite the fact that Rock Island management had been able to move 80% of pre-strike tonnage, at the behest of the Carter Administration, the ICC declared a transportation emergency declaring that the Rock Island would not be able to move the 1979 grain harvest to market.This despite the railroad's movement of more grain out of Iowa in the week immediately preceding the order than during any week in its history. The ICC issued a Directed Service Order authorizing the. The Directed Service Order enabled one-time suitors, via KCT management, to basically test operate portions of the Rock Island that had once interested them. On January 24, 1980, Judge McGarr elected not to review the Rock Island's final plan of reorganization. Instead, Judge McGarr initiated the shutdown and liquidation of the Rock Island Railroad.

Not wanting to preside over an asset sale, Rock Island president. Resigned, and Gibbons took over as president of the bankrupt railroad. Cars and locomotives were gathered in'ghost trains' that appeared on otherwise defunct Rock Island lines and accumulated at major terminals and shops and prepared for sale.Iowa Interstate's ES44AC #513 in "Rock Island" heritage colors rolls through the "Y" at Bureau Junction, IL, hauling coal from Peoria, IL to Cedar Rapids, IA. Painted in Rock Island livery as a memorial. Gibbons was released from the Rock Island on June 1, 1984 as the estate of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad expired. The name of the company was changed to.

In 1988, the company would be acquired by the. Ironically, through the mega mergers of the 1990s the. Railroad ultimately ended up owning and operating more of the Rock Island than it would have acquired in its attempted 1964 merger. The one line it currently does not own (or operate regularly, other than detours) is the Chicago to Omaha main line that drove it to merge with the Rock Island in the first place. This line is now owned and prospers under.The company inspired the song Rock Island Line. , first written in 1934 and recorded by numerous artists. A spur of the Rock Island Railroad that ran beside a small hotel in Eldon, Missouri owned by the grandmother of Mrs. Paul (Ruth) Henning also inspired the popular television show Petticoat Junction. In the early 1960's.

Ruth Henning is listed as a co-creator of the show, along with her husband Paul, who also created The Beverly Hillbillies. The item "ROCK ISLAND RAILROAD LANTERN ADAMS & WESTLAKE COMPANY ROCK ISLAND LINE 1895" is in sale since Monday, July 27, 2020. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Transportation\Railroadiana & Trains\Hardware\Lanterns & Lamps".The seller is "railcarhobbies" and is located in Warsaw, Missouri. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Brand: Adams & Westlake Company