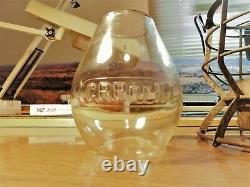

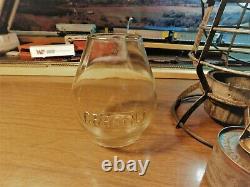

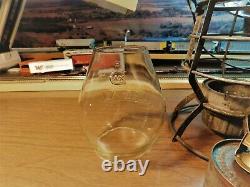

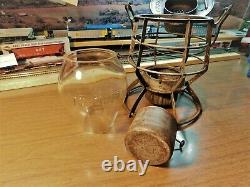

CENTRAL RAILROAD of NEW JERSEY RAILROAD LANTERN DRESSEL C. R. R. Of N. J. 1900

This highly detailed refrigerator car is made by INTERMOUNTAIN RAILWAY COMPANY modeled after the RASKIN PACKING CO. This refrigerator car comes with Precision machined and insulated wheel sets, Authentic scale knuckle-spring couplers and Etched walkways. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. This article is about refrigerated railroad cars in the U. For European practice, see Refrigerated van.

For the Spin Doctors song, see Pocket Full of Kryptonite. The mechanical refrigeration unit is housed behind the grill at the lower right, the car's "A" end.

Was one of the first companies to transport beer nationwide using railroad refrigerator cars. A refrigerator car (or "reefer") is a refrigerated. Refrigerator cars differ from simple insulated. Boxcars commonly used for transporting fruit. , neither of which are fitted with cooling apparatus.Come equipped with any one of a variety of mechanical refrigeration systems, or utilize carbon dioxide. Or in liquid form as a cooling agent. (and other types of "express" reefers) may or may not include a cooling system, but are equipped with high-speed trucks.

And other modifications that allow them to travel with passenger trains. Early attempts at refrigerated transport.Refrigerated trains in the United Kingdom. Railex and other unit trains. #14713, a ventilated fruit car dating from 1893. After the end of the American Civil War.

Emerged as a major railway. Of livestock raised on the Great Plains.Transporting the animals to market required herds to be driven up to 1,200 miles (1,900 km) to railheads. Or other locations in the midwest, such as Abilene and Dodge City, Kansas, where they were loaded into specialized stock cars. Live ("on-the-hoof") to regional processing centers.

Driving cattle across the plains also caused tremendous weight loss, with some animals dying in transit. Upon arrival at the local processing facility, livestock were slaughtered.

Costly inefficiencies were inherent in transporting live animals by rail, particularly the fact that approximately 60% of the animal's mass is inedible. An advertisement taken from the 1st edition (1879) of the Car-Builders Dictionary for the Tiffany Refrigerator Car Company , a pioneer in the design of refrigerated railroad cars. As early as 1842, the Western Railroad of Massachusetts. Designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage.

The first refrigerated boxcar entered service in June 1851, on the Northern Railroad (New York). Or NRNY, which later became part of the Rutland Railroad. This "icebox on wheels" was a limited success since it was only functional in cold weather. That same year, the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad.The first consignment of dressed beef left the Chicago stock yards. In 1857 in ordinary boxcars. Retrofitted with bins filled with ice. Placing meat directly against ice resulted in discoloration and affected the taste, proving to be impractical. During the same period Gustavas Swift.

The method proved too limited to be practical. William Davis patented a refrigerator car that employed metal racks to suspend the carcasses above a frozen mixture of ice and salt.

A Detroit meat packer, who built a set of cars to transport his products to Boston using ice from the Great Lakes. The load had the tendency of swinging to one side when the car entered a curve at high speed, and use of the units was discontinued after several derailments. In 1878 Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design a ventilated car that was well insulated, and positioned the ice in a compartment at the top of the car, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward. The meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car to keep the center of gravity.Low and to prevent the cargo from shifting. Chase's design proved to be a practical solution, providing temperature-controlled carriage of dressed meats, This allowed Swift and Company. Swift's attempts to sell Chase's design to major railroads were rebuffed, as the companies feared that they would jeopardize their considerable investments in stock cars. Animal pens, and feedlots if refrigerated meat transport gained wide acceptance. In response, Swift financed the initial production run on his own, then when the American roads refused his business he contracted with the GTR (a railroad that derived little income from transporting live cattle) to haul the cars into Michigan.

And then eastward through Canada. In 1880 the Peninsular Car Company. Within a year, the Line's roster had risen to nearly 200 units, and Swift was transporting an average of 3,000 carcasses a week to Boston, Massachusetts. Competing firms such as Armour and Company. By 1920, the SRL owned and operated 7,000 of the ice-cooled rail cars.

The General American Transportation Corporation. Would assume ownership of the line in 1930. Of one of the first refrigerator cars to come out of the Detroit.

Plant of the American Car and Foundry Company. (ACF), built for the Swift Refrigerator Line. Live cattle and dressed beef deliveries to New York short tons.

The subject cars travelled on the Erie. Source: Railway Review , January 29, 1887, p. A circa 1870 refrigerator car design. Hatches in the roof provided access to the ice tanks at each end. 19th Century American Refrigerator Cars. Source: Poor's Manual of Railroads and ICC. In the 1870s, the lack of a practical means to refrigerate peaches.Limited the markets open to Samuel Rumph, a Georgia. He was the first to achieve this. His innovations created Georgia's fame for peaches, a crop now eclipsed economically by blueberries. Was born on a fruit ranch near Red Bluff, California on May 30, 1858. His father was Joseph Earl, his mother Adelia Chaffee, and his brother was Guy Chaffee Earl.

By 1886, he was President of the Earl Fruit Company. In 1890, he invented the refrigerator car to transport fruits to the East Coast of the United States. By the turn of the 20th century, manufactured ice became more common. (PFE) - a joint venture between the Union Pacific.

Railroads, with a fleet of 6,600 refrigerator cars built by the American Car and Foundry Company. Maintained seven natural harvesting facilities, and operated 18 artificial ice plants. Their largest plant located in Roseville, California. Produced 1,200 short tons. Of ice daily, and Roseville's docks could accommodate up to 254 cars. At the industry's peak, 1,300,000 short tons (1,200,000 t) of ice was produced for refrigerator car use annually.The use of ice to refrigerate and preserve food dates back to prehistoric times. Through the ages, the seasonal harvesting. Of snow and ice was a regular practice of many cultures. Stored ice and snow in caves, dugouts or ice houses. Lined with straw or other insulating materials.

Rationing of the ice allowed the preservation of foods during hot periods, a practice that was successfully employed for centuries. For most of the 19th century, natural ice (harvested from ponds and lakes) was used to supply refrigerator cars. At high altitudes or northern latitudes, one foot tanks were often filled with water and allowed to freeze. Ice was typically cut into blocks during the winter and stored in insulated warehouses for later use, with sawdust and hay packed around the ice blocks to provide additional insulation.

A late-19th century wood-bodied reefer required re-icing every 250 miles (400 km) to 400 miles (640 km). Top icing is the practice of placing a 2-inch (51 mm) to 4-inch (100 mm) layer of crushed ice on top of agricultural products that have high respiration rates, need high relative humidity, and benefit from having the cooling agent sit directly atop the load (or within individual boxes). Top icing added considerable dead weight to the load. Top-icing a 40-foot (12 m) reefer required in excess of 10,000 pounds.

It had been postulated that as the ice melts, the resulting chilled water would trickle down through the load to continue the cooling process. It was found, however, that top-icing only benefited the uppermost layers of the cargo, and that the water from the melting ice often passed through spaces between the cartons and pallets with little or no cooling effect.It was ultimately determined that top-icing is useful only in preventing an increase in temperature, and was eventually discontinued. Men harvest ice on Michigan's. The ice was cut into blocks and hauled by wagon to a cold storage warehouse, and held until needed. Ice blocks (also called "cakes") are manually placed into reefers from a covered icing dock.

Each block weighed between 200 pounds (91 kg) to 400 pounds (180 kg). Crushed ice was typically used for meat cars.

The typical service cycle for an ice-cooled produce reefer (generally handled as a part of a bice was sporadic) using specially designed field icing cars. The cars were delivered to the shipper for loading, and the ice was topped-off. Depending on the cargo and destination, the cars may have been fumigated. The train would depart for the eastern markets.The cars were re-iced in transit approximately once a day. Upon reaching their destination, the cars were unloaded. This engraving of Tiffany's original "Summer and Winter Car" appeared in the Railroad Gazette just before Joel Tiffany received his refrigerator car patent in July, 1877. Tiffany's design mounted the ice tank in a clerestory.

Atop the car's roof, and relied on a train's motion to circulate cool air throughout the cargo space. A rare double-door refrigerator car utilized the "Hanrahan System of Automatic Refrigeration" as built by ACF.The car had a single, centrally located ice bunker which was said to offer better cold air distribution. A pre-1911 "shorty" reefer bears an advertisement for Anheuser-Busch's.

The use of similar "billboard" advertising. Was banned by the Interstate Commerce Commission. In 1937, and thereafter cars so decorated could no longer be accepted for interchange between roads.Refrigerator cars required effective insulation to protect their contents from temperature extremes. Derived from compressed cattle hair, sandwiched into the floor and walls of the car, was inexpensive, yet flawed over its three- to four-year service life it would decay, rotting out the car's wooden partitions and tainting the cargo with a foul odor. The higher cost of other materials such as "Linofelt" woven from flax.

Synthetic materials such as fiberglass. Foam, both introduced after World War II. Offered the most cost-effective and practical solution. The United States Office of Defense Transportation implemented mandatory pooling of class RS produce refrigerator cars from 1941 through 1948. Experience found the cars spending 60 percent of their time traveling loaded, 30 percent traveling empty, and 10 percent idle; and indicated the average 14 loads each car carried per year included 5 requiring bunker icing, 1 requiring heating, and 8 using ventilation or top icing.

Following experience with assorted car specifications, the United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Association (UFF&VA) listed what they considered the best features of ice refrigerator cars in 1948. Steel cars (vs wood) for better insulation protection and greater rigidity resulting in reduced leakage around doors. A minimum of 4 inches (10 cm) insulation thickness with all insulation protected from moisture.

Cushioned trucks and draft gear. To minimize jarring and bruising of produce. Standardized interior dimensions to allow improved loading methods with standardized containers. Adjustable ice bunker bulkheads to allow greater floor space for shippers using top icing alone. Vertically adjustable grates within the ice bunkers to allow half-stage icing to reduce icing charges where appropriate. Forced air circulation within the car. An additional lining to allow side wall flues circulating air around all cargo preventing contact with exterior car walls. Perforated floor racks providing similar protection and air circulation under the cargo. Provisions for pre-cooling the cars with a portable unit at the loading platforms. The item "CENTRAL RAILROAD of NEW JERSEY RAILROAD LANTERN DRESSEL C. 1900" is in sale since Tuesday, August 10, 2021. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Transportation\Railroadiana & Trains\Hardware\Lanterns & Lamps". The seller is "railcarhobbies" and is located in Warsaw, Missouri. This item can be shipped worldwide.- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Brand: DRESSEL